The only game in town: How better regulations can foster competition and choice for ride-hailing in Toronto

In this edition of Open Mind Economics, I’m teaming up with JJ Fueser with RideFair, a sustainable transportation not-for-profit, to talk about monopoly issues for ride-hailing services in Toronto.

We have written this essay to lay out how more competition between ride-hailing platforms can make life better for drivers and riders. But, perhaps contrary to what you may think, to create more competition the City of Toronto needs to regulate more with better regulation, not less.

The TL;DR:

ride-hailing in Toronto is a bit of a hot mess right now. Platform drivers are generally treated pretty badly by the platforms, and many earn below minimum wage. Some drivers are trying to circumvent this low compensation by accepting rides but then asking riders to pay in cash. This situation raises serious issues for drivers and riders alike.

People in Toronto don’t have many options beyond Uber. Ride-hailing platforms now deliver 80% of all vehicle-for-hire trips in the city, and 91% of ride-hail drivers are licensed with Uber (based on an access to information request we made to the City).

A big part of the problem is lack of competition. When drivers and riders lack choice, they are more vulnerable to bad treatment by the ride-hailing platforms.

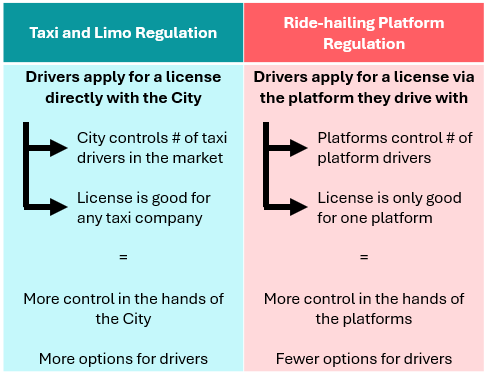

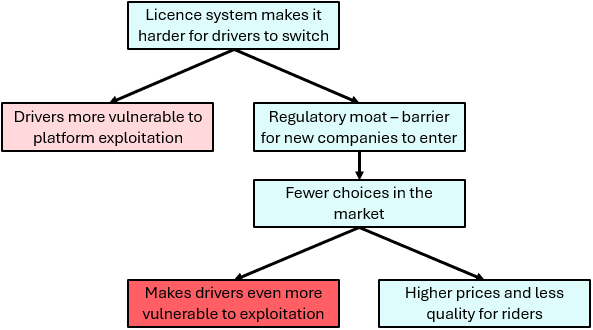

Toronto’s regulations for ride-hailing platforms are a problem. The City’s current ride-hailing regs create a regulatory moat that makes it harder for new platforms to enter Toronto, while also hurting drivers. The core of the problem is how drivers get city licenses. Today, people who drive for platforms can only get a license by applying through the platform, and that license is tied to the platform. If a driver wants to drive for a different platform, they need to apply for a whole new license with that new platform - a process that takes time and costs money. This system makes it hard for new platforms to enter Toronto because they are less able to compete for drivers. With fewer platforms in the city, drivers and riders are stuck with less choice.

The City can’t address driver poverty under the current system. The City remains in charge of when and how many taxi licenses to issue, but on the ride-hailing side, platforms control these decisions. Uber and Lyft have artificially over-supplied the market with too many drivers, so that neither ride-hailing or taxi drivers can get enough work to survive, leading to driver unrest and unsafe practices.

The solution isn’t less regulation, but more of the right kind of regulation. Regulations need to change so that ride-hailing platform drivers get their license directly from the City without having to apply through a platform - as they do in other major markets, like New York and London. On top of that, the City should also act as a central body for security clearances and car inspections for platform and taxi drivers alike. All these changes together will make it easier for drivers to switch between platforms, improving the lives of drivers and also opening the door for other platforms to enter the City.

When regulators (not market players) control licenses and license numbers, they support a vehicle-for-hire market where many alternative service delivery models can be viable: where mom and pop businesses can compete against tech giants and independent contractors work alongside employees. In concrete terms, passengers caught in a snowstorm or a transit breakdown will have options, and won’t be hostage to surge pricing because there’s really only one platform in town.

Earlier this month, a passenger told Global News about how she was stranded in Toronto for 45 minutes at 3 AM. She had refused a ride-hail driver’s request to cancel her ride in the app and instead pay a lower cash fare for the ride. The driver told her he was being paid only $18 for her $62 ride. Since then, other passengers have chimed in with similar stories.

Stories like these capture the precarious state of the “vehicle-for-hire” market in Toronto right now. Many gig drivers earn below the minimum wage. To make more, some drivers are trying to circumvent the platforms by asking riders to pay in cash, which violates their contracts with platforms and leaves them legally and financially exposed, with passengers and drivers unprotected by insurance and untrackable. While taxis still offer transparent, regulated rates based on time and distance, there are far fewer available than ten years ago. For many passengers, the Uber/Lyft duopoly is the only game in town.

Uber and Lyft were once welcomed as a disruptive competitor to taxis. Using digital technologies to bring the wholesome “sharing economy” to cities across Canada, these platforms promised more choice, lower prices, and shorter wait times for riders.

Ten years later, these platforms have shown their ability to disrupt the markets. But the promise of greater choice and competition has not been fully realized as Uber has come to dominate several cities across Canada, concentrating control over pricing and pay for private passenger transportation under a single company - and helping keep in place regulations that insulate them from competition.

Here, we lay out the case for Toronto City Council to end self-regulation by dominant ride-hailing players. The current rules, with driver licensing done by the platforms, were implemented a decade ago in the early days of ride-hailing. Now we know more: licensing-by-platform deters new entries and so harms both drivers and passengers. Residents and drivers both bear the cost of a chronic oversupply of ride-hailing vehicles.

How dominant are the ride-share platforms in Toronto?

In Toronto, as in many other markets, Uber now controls the vast majority of rides. Ride-hailing platforms now deliver 80% of all vehicle-for-hire trips in the city, and 91% of ride-hail drivers are licensed with Uber (based on an access to information request we made to the City). Overall, in Canada an estimated 78% of consumers using taxi services used Uber. Uber’s market power gives the company an outsized role in controlling fares and driver compensation.

Changes in US Employee Wages vs. Uber Driver earnings, 2022-2023 (Sherman, 2024)

While fare and pay data are scarce for Canadian markets, Uber prices in the US have risen faster than inflation since the onset of the pandemic. At the same time, driver pay has dropped, decreasing by an estimated 17% in 2023 alone.

By 2023, a community-led study in Toronto using company and city data estimated that platform drivers’ median hourly earnings were about $6.37 - less than half of Ontario’s minimum wage (now $17.20/hour).

Beyond price, the growing dominance of these platforms has other major downsides. Platforms have replaced a portion of public transit trips, contributing to greater traffic volume in downtown Toronto and lowering the fare income on which our transit system depends. Pre-pandemic, ride-hailing platforms (which the City of Toronto calls Private Transportation Companies) represented as much as 14% of downtown traffic. One of the least efficient modes of passenger transportation (even when electrified) they have also contributed to rising emissions from transportation.

How did we get there? In the case of Toronto, a lopsided regulatory regime that protects established ride-hailing platforms like Uber and Lyft from potential competitors has a role to play. The consequence of this regulatory dysfunction is less choice for consumers, but the negative impacts are most profound for ride-hailing drivers. The current system makes drivers more susceptible to exploitation, getting paid less than they should while being vulnerable to termination (“de-activation”) without notice or explanation.

Nearly a decade ago, The Competition Bureau, Canada’s competition authority, called for municipalities to take a “lighter” approach to regulating vehicles-for-hire to accommodate these new, digital business models. But to truly enable competition in Toronto’s market, the city needs to change ride-hailing regulations to enable more competition in the market - principally by removing market leaders from their current quasi-regulatory role, and reinstating the City as the arbiter of public safety and consumer protection. With the current review of Toronto’s vehicle-for-hire bylaws, scheduled for December 2024, city leaders have the opportunity to make this happen.

Toronto’s regulatory saga

2016 was a pivotal year for taxi regulation because it was the year that Uber first began legally operating in Toronto under a new set of regulations specifically for platforms.

Prior to 2016, the City only regulated taxis and limousines. It issued a set number of licenses for drivers and regulated fare rates. Following a long review of the City’s regulations ending in 2014, City staff recommended that the total number of licenses available in the market and fares be reassessed every two years to balance the supply of drivers and the demand for rides. This balance would ensure that drivers earned a fair, living wage while also ensuring that riders would get picked up in about 9 minutes or less. Without this oversight, experience showed that more drivers would seek licenses than the market could support, resulting in plummeting incomes for drivers.

In 2014, just months after Toronto City Council passed new taxi regulations, Uber began operating illegally in the city. Uber’s goal, realized through aggressive lobbying, was to work with the City to develop a regulatory system that was different from the current system regulating taxis and limos. It wanted to be recognized as a technology firm, not a taxi company. The result was two related but parallel regulatory systems -- one for taxis and limos and a second for Uber and other ride-hailing platforms.

Under the 2016 ride-hailing regulations, the platforms were exempted from many of the safety, vehicle inspection/licensing, accessibility and environmental regulations that applied to vehicles for hire. Driver training requirements were scrapped across the board. The taxi sector raised fairness issues, so Council watered down environmental standards in 2019 for taxis as well.

The new ride-hailing regulations also handed over licensing powers to the platforms. For ride-hailing drivers to obtain a license, they had to apply through the platform rather than directly to the City like taxi and limo drivers. If a driver wants to drive for a different platform, they need to apply for a second license with the other ride-hailing company. Obtaining this second license is possible, but can create a significant barrier for drivers. The Uber website explains that to become a driver it takes up to 20 days for the City to issue a license, it takes between 3 to five days to complete background safety screening, and drivers need to provide a vehicle inspection that is no more than 36 days old.

Furthermore, the ride-hailing platforms effectively have the power to issue as many licenses as they want, in spite of a 2016 resolution of council requiring that the City “manage the number of ride-hailing vehicles, as necessary”. Taxi licenses, by contrast, have remained capped at levels set in 2014.

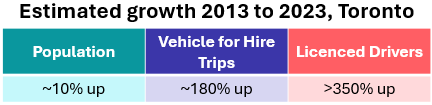

Not surprisingly, with the platforms controlling how many platform drivers operate in Toronto, the total number of drivers for hire on Toronto streets has increased significantly. Within the first five years of ride-hailing platforms operating in Toronto, the number of vehicles for hire grew by 500%, with ride-hailing trips growing by 180% from 2016 to 2019 alone. Based on information we got from an access to information request and data from the City, by 2023, the total number of vehicle for hire trips had increased by 183% over 2013, while the number of licensed drivers had increased by over 350%.

As of today, Toronto’s continues to have these two parallel regulatory systems for platforms on the one hand and taxis and limos on the other. The ride-hailing system gives platforms like Uber a lot of power. They, rather than the regulator, act as stewards of public safety, collecting and vetting important driver documents, such as proof of adequate insurance, proof of driver training and background checks. They can both control the number of drivers available in the market while limiting the ability of drivers to move between platforms.

The current regulatory system has made it significantly harder for new platforms to enter - precisely at a moment when other platforms, including a local startup, are exploring the Toronto market. The setup has serious implications for the state of competition in Toronto’s vehicle-for hire market, harming riders and, most profoundly, drivers.

Competition, choice, and driver wellbeing

Regulatory moats are regulations that protect established, incumbent businesses by making it more difficult for new businesses to enter the market. When, through lobbying, Uber worked with the City of Toronto to craft regulations for the ride-hailing industry, it created a regulatory moat that makes it far more difficult for other platform companies to enter the Toronto market and offer an alternative. The core of the problem is that licenses for drivers can only be accessed through the platforms. Because of this setup, it is more difficult for drivers to switch between platforms, which has consequences for drivers, potential competitors, and riders.

When drivers are unable to easily move between platforms, it makes them more vulnerable to exploitation by the platforms. They can’t just simply move on to another platform when they are mistreated. But the problem for drivers is exacerbated when there are fewer platforms they can drive for, which is also a consequence of the system. Because it is more difficult than it needs to be for drivers to switch platforms, it is more difficult for competing platforms to enter the market. As a result, drivers have fewer platforms to drive for and riders have fewer options to choose from.

Ultimately, improving competition in the market for vehicles-for-hire isn’t about simply increasing the number of drivers operating in Toronto. In actuality, competition in this market is about increasing the number of platforms so that both riders and drivers have the choice and the freedom that comes from it.

Platform dominance causes other problems

The dominance of Uber and other driver platforms in Toronto and cities across the globe has come with other competition-related issues.

Misleading advertising by the major platforms remains a key issue. For example, platforms routinely claim that drivers earn a median of $33 per engaged hour, but do not explain that this number does not take into account time not spent actively driving riders (i.e., engaged time), expenses like fuel and parking, or even that typical earnings can range significantly in a market. In the US, the Department of Justice found Lyft guilty of “luring” drivers with false and misleading claims about earnings. The US Federal Trade Commission (FTC) has taken a hard line on deceptive marketing by platforms. The Competition Bureau needs to scrutinize these potentially misleading statements.

More recently, Uber and Lyft in Toronto have also implemented “personalized pay”, which is an AI-based fare and pay system for drivers. Whereas taxi fares are carefully regulated by the City, aside from a minimum base fare, Uber and Lyft can set any rates they want, and can hike prices and cut fares for the very same ride. If the lion’s share of rides in Toronto are supplied by platforms using AI-based pay and fares, consumers and drivers have to take whatever they dish out. Researchers have also documented how algorithms can punish drivers for refusing trips (even if they are poorly paid or dangerous), and can incentivize drivers to stay on the road through elusive monetary quests. While the Province has introduced legislation to increase the transparency of pay practices within the gig economy, it remains to be seen how enabling regulations will address these issues.

However, market concentration in the vehicle-for-hire industry impacts these issues as well. The dominant position that two platforms have in the market means a lack of competition that could keep them and their pricing in check.

What should the City do?

Simply put, Toronto City Council needs to dismantle the regulatory moat that protects Uber and Lyft from competition in the market. It should revise regulations so drivers have freedom to move between platforms like taxi and limo drivers have to move between brokers. This change will help create better pay and working conditions for drivers, and more choice for consumers.

Regulators, not platforms, should be in charge of licensing

The City needs to take back licensing power from the platforms. Instead of forcing drivers to spend money and time obtaining a separate license for every platform every year, drivers could apply for or renew a single license issued directly by the City. Drivers could then use that license to work with any platform or even dispatchers of taxis or limos.

To create the ideal conditions for competition between driver platforms, the City could develop a centralized driver-application system that provides a single doorway for drivers to apply for any platform. Today, when applying to drive for a platform, drivers also need to undergo security screening and submit a vehicle safety inspection to the platform, in addition to getting a license. All dimensions of this application -- security screening, vehicle inspections, and licensing -- could be harmonized across the platforms and become the responsibility of the City to oversee. Requiring ride-hailing vehicles to be licensed and inspected (already required of taxis) would help deliver safer rides. The city has already made drivers’ licenses non-transferable, avoiding replicating the old medallion system, where licenses became a tradable commodity.

This centralized approach is not new, and Toronto has implemented something similar for short-term rentals. There, the City issues licenses to hosts wishing to list on platforms. Once hosts receive the City-issued permit, they can rent out space on any licensed short-term rental platform in Toronto. Similarly, drivers should receive a ride-hailing license from the City, and with this unique individual license number, should be able to drive on any licensed platform. Like in the short-term rental space, this program can be run on a cost-recovery basis, charging ride-hailing companies a yearly license fee, scaled to account for the number of drivers they employ.

To fund this centralized driver-application system, the City would need to significantly increase the fees it charges platforms. Today, platforms pay $20,000 per year to operate in Toronto. In contrast, London, UK, charges average annual fees of £464,000 if the platform has more than 10,001 drivers. Likewise, in New York City platforms dispatching more than 10,000 drivers must pay US $380,000 for a two year license. For context, prior to the pandemic Toronto had approximately 88,000 licensed Uber drivers, according to an access to information request we submitted. The City of Toronto should substantially increase the fees it collects from platforms to operate in the City and use these fees to fund the centralized system

Benefits of a City-led, centralized driver-application system

First, having the City take on the role of issuing licenses opens up the market for dispatchers and platforms to compete for drivers, which gives drivers greater ability to move if they are mistreated or underpaid. It’s also good for new platform companies that want to enter the Toronto market and compete against Uber and Lyft. It gives them access to the pool of Toronto drivers they need to enter the market at a scale that enables them to compete effectively against Uber.

Second, with driver licensing back in City hands, the City can determine the optimal number of licensed vehicle-for-hire drivers on our roads. By taking back control, the City can better manage congestion, emissions, and road safety. Controlling the total number of licenses can also help ensure that drivers have enough work and that the rates they get paid are not suppressed by an over-supply of drivers in the market. As Toronto City staff noted in 2014, “[t]oo many taxicabs can cause traffic congestion and nuisance … having too many taxicabs negatively affects driver incomes which can result in risky driving habits to secure fares.”

In the largest study of its kind to date, researchers tracked changes in earnings for taxi and ride-hail drivers across the US following the introduction of ride-hailing services between 2010 and 2016. While the introduction of ridesharing resulted in an earnings decrease for drivers in cities where governments did nothing to regulate the number of taxi-type licenses issued, the decrease was smaller or non-existent in cities with strong regulations, like Los Angeles, Chicago and New York City.

Overall, when cities control licenses and license numbers, they support a market where many alternative service delivery models can be viable: where mom and pop businesses compete against tech giants and independent contractors work alongside employees. In concrete terms, passengers caught in a snowstorm or a transit breakdown will have options, and won’t be hostage to surge pricing because there’s really only one platform in town.

Promoting choice, protecting drivers and ensuring consumer safety

At first glance, the regulatory status quo seems paradoxical: there are too many drivers participating in Toronto’s vehicle-for-hire market, but at the same time, there is insufficient competition. But competition principally occurs at the level of the platforms that dispatch the rides - for the vast majority of trips, platforms exclusively set the fares for customers and determine pay for drivers.

In the past, the Competition Bureau was bullish on these platforms as creators of transformative competition that would disrupt the taxi market. It advocated for municipalities to change regulations to make it easier for platforms to operate in cities and compete against taxis. But today, we face serious, but different competition issues than the problems considered by the Bureau a decade earlier. The solution isn’t less, but smarter, regulation that actually supports the market and serves the residents of Toronto better.

Our opening story, where a ride-hail passenger described how her driver asked her to cancel her app-sourced ride for a cash fare, shows dysfunction in our current system and suggests these types of risky behaviours may be on the rise. On the part of drivers, a spontaneous driver protest broke out at the Pearson Airport rideshare lot as driver anger over Uber’s AI-based pay practices boiled over.

The precarious labour on which dominant ride-hailing platforms were built are threatening to undermine the industry. While tinkering with pay for “engaged time,” no party - not the City, not the Province and not the platforms - have done anything to ensure that participants - be they independent taxi drivers, drivers with brokerages or ride-hail drivers - can carry on viable businesses. But the Province, through the City of Toronto Act, explicitly gives the City the authority to license drivers and set maximum limits on the number of licensed drivers. It’s time for the City to use its available tools to steer the vehicle-for-hire industry back to stability, protecting safety and choice for both drivers and consumers.